Renaissance Humanism

The Renaissance as a period of time between the 14th and 17th centuries that was marked by a sense of revival and “rebirth”. This regenerative period was captured by ancient texts and the recirculation of lost knowledge. The Renaissance moved Europe out of “The Dark Ages” and into a time of progress and newfound wisdom. Humanism, in its most basic sense, is a system of thought that is moved from holding the divine as most important and instead views the individual or the human to be the epitome of value. This period was marked by a desire to pursue the humanities and to learn from them in order to progress as a society. During this period the idea of humanism became popular and permeated the minds of scholars in the academic world.

“The central focus of Renaissance Humanism was, quite simply, human beings. Humans were praised for their achievements, which were attributed to human ingenuity and human effort rather than divine grace. Humans were regarded optimistically in terms of what they could do, not just in the arts and sciences but even morally. Human concerns were given greater attention, leading people to spend more time on work that would benefit people in their daily lives rather than the otherworldly interests of the Church” (Cline, 1).

It seems only natural that humanism would be a product of the Renaissance, purely because it was a focus of ancient texts. Humanism not only affected the people that lived during the Renaissance but also those who engage in historiography and the study of history in the present day.

Contradiction to the Middle Ages?

One of the key components of the Renaissance is the idea of its complete contradiction to the Middle Ages. The whole point of the Renaissance was after all to move from the stagnant middle ages onto a period of discovery and progress through utilizing ancient texts and philosophies and bringing them into the mainstream academia. However, the Renaissance and the “rebirth” of ancient texts would not have been possible without the middle ages.

“Second, I found that the Renaissance historians were far more indebted to their medieval predecessors than might be apparent from their conscious rebellion against them; and I was therefore obliged also to consult some of the equally abundant scholarly literature on the subject of medieval historiography. To be sure, I found medieval historiography to be very different from the humanist historiography of the Renaissance… Nevertheless, the medieval historians provided their Renaissance successors with much of the specific information about the centuries in which they had lived and written… Still more important, they developed a form of historical writing -a series of single events listed opposite a corresponding notation of dates in no other order than that of chronological succession- that continued to be used, by humanists themselves as well as by writers whose cultural formation was still basically medieval in content, throughout the period of the Renaissance” (Cochrane, xv prologue).

So, although the Renaissance humanists were attempting to get away from the middle ages, they were necessarily equipped to do so by the middle age thinkers. It is interesting to think that the whole motivation of the Renaissance was to get away from the middle ages. The Renaissance thinkers even went so far as to coin the term “middle ages” as such. They believed in their personal ability to progress and held their own human accomplishments in high regard. This shows their reliance on humanistic principles and the overall importance and impact of humanism on the Renaissance and historiography. The Renaissance without humanistic principles would not have changed the world as dramatically as it did.

Secularism

Secularism was one of the primary principles through which Renaissance humanism acted. Secularism in it’s roots is just the separation of an entity from religious institutions or religious influence. Now, secularism within the Renaissance was not necessarily practiced in these clear cut lines. Traditional secularism is primarily focused on life totally without the affect of God or His institutions. Renaissance secularism differs from the traditional in that it is more liberal (or perhaps conservative depending on personal opinion). The thinkers of the Renaissance did not operate with an atheistic view, to do so would have been social suicide. They would have had trouble gaining economic and social connections because it was looked down upon when someone did not believe in or follow God. They rather operated without God in their daily lives, ignoring the present religious institutions.

The Renaissance was a rebirth, and in that sense, a refocus on the earthly and present. The focus of academic society moved from religion and theology and into the physical and present studies. They began to focus on language, prose and poetic literature, rhetoric, and moral philosophy. This could also be seen in the political and social world. The humanist man during the Renaissance was moving from traditional occupations in the clergy and out in the countryside to more urban style occupations. These people pursued careers in business, commerce, banking, town planning, architecture, the arts, administration, and government. These people were not necessarily opposed to God in anyway, they were rather focused on the earthly and the things that could progress their social status.

“The latter is important to mention because although the orientation of these disciplines is so clearly ‘humanist’ -directed away from the eternities of ‘heaven’ toward the varying, contingent, complex human world -it does not mean Renaissance humans were, in the main, anti-God (or atheistic) or even anti-religion” (Lemon, 80).

The Renaissance humanist, with all of his secular ideal of his social life, was often not opposed to religion, just apathetic to it. This is important because it shifts completely from the Middle Ages and the thought process that had dominated Europe for multiple centuries. One important distinction between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance with regards to secularism is how it related to the social world with regards to the Divine.

“They considered the realm of the secular to be important only to the extent that it was a reflection of the divine. And they could find no other connection between one event and another than what they might be able to deduce from the words either of ancient or of modern prophets” (Cochrane, xv prologue).

This perfectly shows the difference between the two periods. The middle ages were concerned with the relation of their social action between themselves and the divine while the Renaissance was concerned with the relationship between their social action and others.

Individualism

Individualism is a key part of the Renaissance and is especially important to the humanist movement during the Renaissance. Individualism during the Renaissance focused on the individual pursuit of knowledge for each person. It also focused on individual achievement and individual talents regardless of the rest of society. When looking back upon Renaissance history we are for the first time able to see more of the intricate details of society and the role of the individual in this society.

“A problem for any interpreter of late medieval or early renaissance Italy is the current imbalance in historical scholarship with its passion for economic and social history. Over the past years only modest interest has been displayed for the systematic increase of the small stock of psychological insights into the emotional characteristics of this period” (Becker, 274).

The individual present in the Renaissance is someone who is calling for us to understand them. With the focus of historians over the years only on the broad subject matter within history we have not been fully able and competent to understand the depth and the motive of the individualistic person.

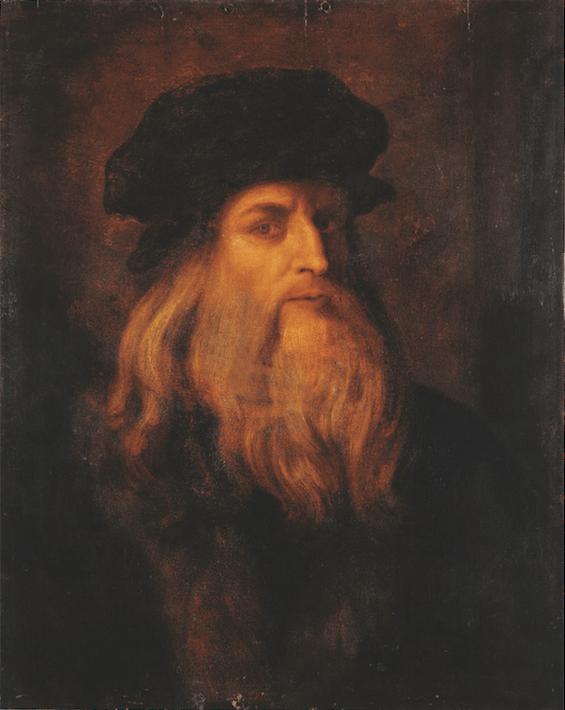

“Another feature of Renaissance culture in general which helped clear the ground for new perspectives on the ‘meaning’ of history was the growth of ‘individualism’, a term used by Burkhardt to capture not only the emergence of certain people remarkable for the variety of their talents and interests -the famed ‘Renaissance man’ such as Leonardo Da Vinci -but also a more widespread individualistic spirit amongst people in general. Increasingly those in the developing commercial cities of Europe, loosened from a previously church-dominated rural way of life, began to think for themselves” (Lemon, 82).

For the people in Europe during the Renaissance, the ability to move away from the church and from ideals that were forced upon them to new unhindered ways to think was incredibly liberating. Individualism not only was a facet of Renaissance humanism but also seems to be the main product of the time. The Renaissance is defined by the rise of the individual in society and the fall of institutionalization.

So What?

The Renaissance will always be known as a time of revival in the arts and in academia in general. But how does this all relate to historiography? How can we see a change in historiography before and after the Renaissance? One of the main ways that we might see this change is within the rise of the individual. Moving even slightly from large meta-histories that talk on huge institutions and huge events to the individuals that made these events happen within the microhistories (studies of smaller events and individual people). We are able to see for perhaps the first time how individuals are the coal to the huge fire of history.

“Even in the late twentieth century, when historians have learned to ask new questions, to study new subjects, and to adopt methods of research unheard of four centuries earlier; even in the twentieth century certain of the peculiar traits of Renaissance historiography may still occasionally be observed, even in the works of those historians who are the least conscious of a debt to Renaissance humanism” (Cochrane, 492).

The Renaissance affected every part of the humanities and especially the writing of history. Within secularism we can see the freedom of the writer able to express opinion without the guidelines of the church hovering over him. We can see a shift from institutionalization in writing into the domination of the individual. We can also see the shift from religious writing dominating the scene in Europe into the introspective and socio-political spheres of writing. All of these shifts in influence on writers during the Renaissance opened the door for the writers that would come later in history. Like Cochrane said in the quote above, many of the modern day writers are not aware of the influence of Renaissance humanism on their own writing. Without this period of rebirth and revival we may still be completely influenced and oppressed by institutions in our writing and we might not be able to have our own unique opinion without the influence of others infiltrating that idea. The Renaissance may be seen as one of the major paradigm shifts in the history of history. Without it historiography as we know it would be completely different.

Bibliography

Wilde, Robert. “A Guide to Renaissance Humanism.” ThoughtCo., 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/renaissance-humanism-p2-1221781.

Cline, Austin. “Renaissance Humanism.” Learned Religions, 2017. https://www.learnreligions.com/renaissance-humanism-248119.

Becker, Marvin B. “Individualism in the Early Italian Renaissance: Burden and Blessing.” Cambridge University Press 19 (1972). https://www.jstor.org/stable/2857095?seq=2#metadata_info_tab_contents.

Cochrane, Eric. Historians and Historiography in the Italian Renaissance. Chicago (Ill.) University of Chicago Press, 1985. https://unm.on.worldcat.org/search?queryString=no%3A+1014618018#/oclc/1014618018.

Lemon, M.C., “Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students”, Routledge, 2003.

2011 words. /essays/early-modern/renaissance-humanism.html