Historical Fiction or History

Why not both?

Sitting in a classroom, yours eyes glazed over as the teacher drones on with fact after fact is their force-feeding or history. Sound familiar? Does it really have to be so dry, so…boring? Is there another way to garner our interest and draw us, willingly, into what is really a very exciting world? The answer is yes, the tool…Historical Fiction.

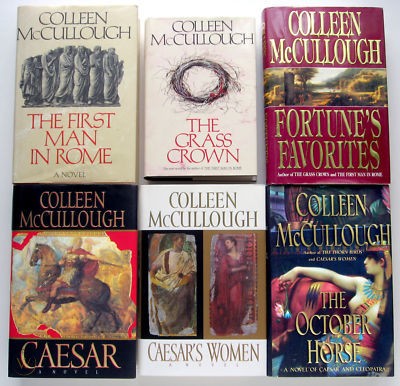

Novels, movies, and television entertains us and help us escape from the world for a time. They expand our understanding of what is and what can be. They untether us from reality and thrust us into an expanse of diverse and fantastic worlds with engrossing characters. Works like HBOs Rome and Collen McCullough’s Caesar (part of the Masters of Rome series) can both entertain and educate, in some cases unwittingly, by drawing us into their worlds.

Before diving deep into the world of historical fiction, let’s look several genres (with print, visual, and audio examples) to expand our understanding and appreciation of the of the tools available to writers and the world of history.

What the Genres?

- Narrative History or Academic History - This form of historical writing is the one we are most familiar with, having been bored to tears with it throughout those torturous years from elementary through high school. The ‘facts’ of narrative history were beaten into our heads. Rote memorization and villanization of any other type of narrative really threw a wet blanket on anything really interesting or exciting in history, reminding us all of [Ben Stein]’s(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ben_Stein) lecture on the Smoot-Haley Tariff Act in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Minimizing creative license in the narrative, adding elements that cannot be supported by historical sources or the embellishing of fact to enhance the reader’s emotional investment in the narrative, is what had us mainlining No-Doze all through high school. This genre can include biographies and memoirs. 12

- Frederick Jakson Turner’s “Frontier Thesis” (book)

- History Channel’s Modern Marvels (television)

-

L. Jay Oliva’s Peter the Great (book)

- Creative History or Nonfiction - Creative History, or non-fiction, borrows from the academic narrative and interjects elements that may not be supported by historical sources, yet is consistent with the events and larger narrative.3 The information in these books is as accurate and verifiable, but the language and narrative techniques provide readers with a more literary experience and presumably a greater emotional connection with the book’s content. 4

- Alex Haley’s Roots (book and television)

- Nadezhda Durova’s The Cavalry Maiden (book)

- Historical Fiction - Now, this is where history started to really ‘grab’ us. Those exciting stories that drew us in and made us feel as though we were living them. Accurate historical settings, characters and larger events, with the addition of elements created by the author that cannot be supported by the historical record, makes historical fiction interesting. It strives “for the story that underlies reality and thus become an imagined reality” 5[^HistFic vs Hist].

- HBO mini-series Rome (television)

- Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace (book)

-

Gordon Lightfoot’s “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” (song)67

- Alternate History - With history full of possibilities, should one event changed or on person be removed, we get to imagine Alternate History. These are storylines that have a point and time in history as a point of origin, but then diverge from the historical timeline to present a “what if” scenario to the reader, exploring a history that might have been [MerriamWebster]8.

- Philip K. Dick’s Man in the High Castle (book and television)

- Robert Harris’ Fatherland (book and movie)

-

BBC’s The Black Adder (television) 9

- Fictional History - Imagine Earth populated by humans living underwater and breathing through gills. Set in a real place, but completely separate from reality, these are histories do not qualify as alternate history. This genre is often confused with Historical or Alternative Fiction. 10

- J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (book and movie)

- Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (book, movie, and television)

-

George Orwell’s 1984 (book)

- Fiction - • Whether Science Fiction (SciFi), romance, or fantasy, these are worlds and events which are created by the author, wholly (not HOLY) or in part. Vast and immersive, we find ourselves easily lost in these fictional worlds. [^Brittanica]1112

- Frank Herbert’s Dune (book, movie, television)

- Suzanne Collins’ Hunger Games (book and movie)

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (books and movies)

We generally understand that history studies the past,13 but nothing says it needs to be dry and boring (high schoole flashback). Let’s move forward, and look at how history can be inviting and exciting, and the role historical fiction plays in the adventure.

In all fairness, the least useful genres, in terms of studying of history, are Fiction, Fictional History, and Alternative History. While interesting, in their own right, they do nothing to expand our understanding of or bring us closer to the historical record. So, let’s move to the other three: narrative history, creative history, and historical fiction.

To simplify matters, and because the lines between them can be indistinct, I’m will simply use ‘historical fiction’ to refer to both historical fiction and creative history. In fairness, historical fiction is part of a literary spectrum ranging from fiction to narrative (academic) history, with several stops along the way. Each of these is part of a spectrum with none holding a fixed position, each arguably blending into the next.

What is historical fiction?

Historical fiction, while based in past events and notable characters, uses fictional interactions and secondary characters to create a vibrant and vivid narrative to engage you, the reader, similar to creative fiction. The American Revolutionary War epic The Patriot uses fictional elements and dialogue to ensnare our interest in the larger story of America’s fight for independence. Benjamin Martin is an amalgam of several historical figures, giving a picture of a man forced into a war of insurgency by the death of his son. This injection of dialogue, minor events, and composite figures, though not supported by historical primary sources, increases our involvement and interest in the story without altering the historical narrative. [^HFwiki]

Lost in Doctrine

Each of us, remembering our high school World History class, knows how dry and uninspiring narrative histories can be. Names, dates, locations, and people are at the very center of what we were all taught history is ‘supposed to be.’ The facts, just the facts, please. No wonder many of us despised these classes, with several falling asleep (no finger pointing here). I point you back to the earlier Ben Stein example.

Without realizing it, we were indoctrinated into the Euro-centric14 and nationalistic histories that colored our understanding of history and the world. Even today, Euro-centrism and nationalism pervade what is taught to children in schools in the western world. Now, what if the method and tools of teaching history were turned upside-down? Enter historical fiction.

Similarities

While narrative history and historical fiction differ, they also have much in common. Each depends on an in-depth knowledge of history’s critical elements: people, places, and period. This knowledge comes from extensive research into each facet of the overriding narrative arc. This is done to convey the most accurate and believable depiction of history. Without the gathering of the credible source material, the author fails to reach us effectively and credibly. It is this common foundation that establishes the value of the content beyond that of mere entertainment.

What is the role of historical fiction?

For centuries we have relied on the traditional ‘narrative’ in the academic world. Whether Greek (Ptolemy, Timaeus), Roman (Tacitus, Livy, Pliny), Christian (Augustine, Eusabius Pamphili, Socrates of Constantinople, Caesar Baronius), or [modern] (Leopold van Ranke, Frederick Jackson Turner, Voltaire), historians have rejected the idea of anything other than the ‘facts for fact’s sake_,’ leaving us with the narrative style we have known throughout our schooling. While the ‘facts’ are central to the very nature of historical studies, there is a lack of emotion and personal investment for us as the readers. Wait, don’t nod off yet!

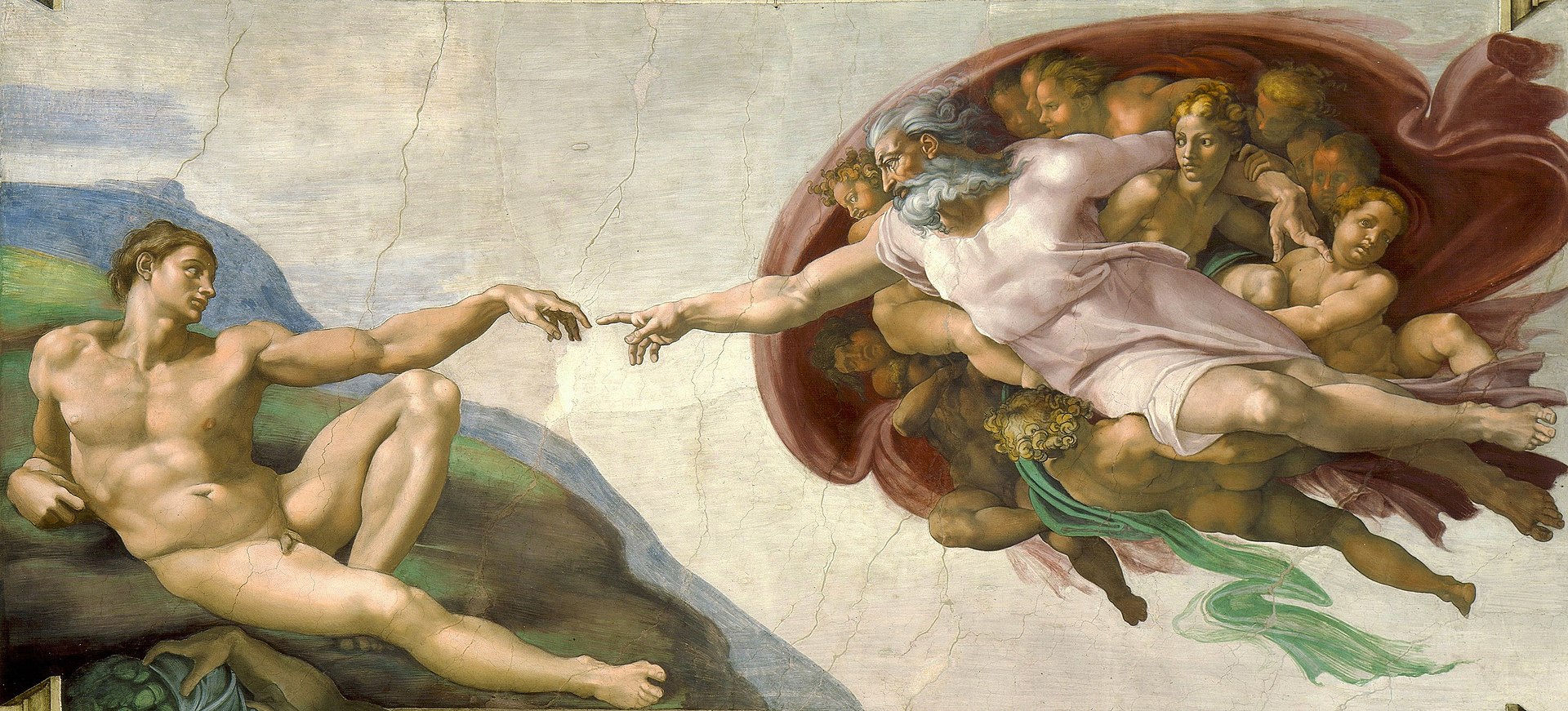

Historical fiction goes beyond the absolute historical record, interpolating and intuiting the missing dialogues and minor events. It adds a vibrancy—life—that has long been missing from the chronicle. We have all heard tales of Hercules, Apollo, and Icarus. Early civilizations—Greeks, Romans—used myths to inform and teach about their origins and place in the world. This was done to equal effect within Christendom, with the Old and New Testament stories of the Bible, beginning with the creation myth in the “Book of Genesis”. These stories seize our interest because they are exciting. Then, as now, these fictions tell us about who we are and where we come from. These works are, arguably, more fiction than fact, and this is what grabs our attention sucking us into the story. While they are at some level fiction, there is little debate regarding their value in studying of history. 1516

Historical fiction is different. In fact, it is more interesting and possibly more historically accurate, by many accounts, than the Greek, Roman, or Christian mythologies. While interesting, these mythologies provide little historical substance. In this way historical fiction serves a greater purpose to us as readers of history, beyond mere entertainment. We strive for accuracy and detail, which is at the heart of historical fiction, and hunger for the moments that it creates.[^creanon]

Great examples of this [Colleen McCullough]’s(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colleen_McCullough) Masters of Rome novels and HBOs Rome. These well-research works enliven the world of pre-Christian Rome huring us into the excitement and intrigue of the Rome of Julius Caesar and Augustus Caesar, by using dialogue, personal interactions, and transitional events. While not drawn directly from the historical record, these contrived elements enhance the histories of the primary actors. McCullough’s books tell of the rise to power and rule of Roman men whose names are familiar to us: Gauis Marius (The First man in Rome), Lucius Cornelius Sulla (The Grass Crown), Gaius Julius Caesar (Caesar), Augustus Caesar. While not academic narratives, these works instill life and vibrancy to history that lures us into the world of these men of Rome.

Narrative and the ‘Rosenberg Paradox’

In examining the utility of historical fiction in the study of history, we must take a brief look at the primary tool used in history and every other field of endeavor: Narrative. Human history, even our lives today, is wrought with narrative. But what is narrative? Can history or anything else, for that matter, be communicated without it?

Narrative is that process of conveying information through a story. With the exception of numerical data, everything we say and write is part of a narrative. We are story tellers at heart, and it is through stories that we add meaning to events, and data. Though argued by many, including Michel Foucault, Jean-Francios Lyotard, and Alun Munslow, it is Alex Rosenberg (a Professor of Philosophy and author of two historical novels) who makes the most direct assault on narrative’s utility painting a bold target on historians use of the tool.

Rosenberg claims that narrative clouds our understanding of history, tainting it. Though deeply ingrained in who we are as human beings, narrative is something that we must excise from how history is told, adopting the more sterile scientific method to communicate the past 17.

Ironically, the very vehicle they wish to cast aside is precisely the tool they use communicate information and enhance our understanding. Rosenberg admits that he, as much as anyone, is a “victim of narrative.” Like Rosenberg, historians, philosophers, doctors, accountants, and scientists are dependent on narrative to share their ideas. Without narrative information loses meaning and falls on deaf ears. Therein lies the paradox of Rosenberg’s argument: with narrative information (history) is tainted; without it there is no meaning, it devolves to data points.

Assessing the value of historical fiction?

Clearly, we can’t accept these works as historical ‘gospel.’ With the addition of fictional elements, we have to divine fact from fiction. Even so, the factual portions of these works are enhanced by the inclusion of the fictional aspects. Provided we understand and recognize the difference between the history and the fiction, historical fiction can present a more significant opportunity to grasp and become involved in the story that narrative accounts are unable to accomplish.

A place for historical fiction in the study of history?

By its very nature, historical fiction is part of the study of history. Building upon subject matter research, these works extend the reach of traditional narrative histories. Authors of the historical fiction are, to varying degrees, committed to building a world based on factual, credible evidence to construct a firm historical foundation for their works. Without this foundation, the author and work are lacking in credibility and cast us into a world of fantasy. While still engaging, it fails to enhance our understanding of the past and draw us into a more in-depth search into past events, places, and personalities.

Expanding interest in history?

The author’s passion for the subject and their dedication to research and accuracy of the presentation carries over to us, the audience. These elements enhance the study with the development of dialogue and characters we are unable to reconstruct from historical sources. They add to our ability to visualize the people, places, and events in a historical context. Historical fiction gains our emotional investment by creating an active and engaging environment, acting as a tool to increase our interest in the historical topic the author is presenting.

Sign on the Dotted line?

Though interspersed with fictional elements, These works increase our personal involvement in history, driving us to read and investigate the subject through more traditional academic sources. Reaching into the primary source material, these inquiries into the past increase our interest and involvement in history. Integrating works of historical fiction (and creative history) into the academic environment provides a means of drawing more students into the academic study of history.

In Closing (not your eyes!)

The study of history can be quite dry or very engaging. Looking back on the past not only tells us about where we came from but can inform us about where we are going. It helps us to understand ourselves and those around us. It builds skills that serve us in virtually every field of endeavor. Through research, organization, language, and argumentative writing, we are better prepared to face the challenges of the ‘real world.’ But is something missing?

With the addition of well-researched historical fiction to the study of history, we are adding a creative spark that may well be lacking in the field. Creativity manifests itself in many ways, such as invention and expression. Creativity nourishes, expanding our visions, and drawing us closer to who we are. Should we now deny the very essence of creativity in the study of history? How can we deny our nature as an imaginative and resourceful species?

| [^Brittanica]: “Fiction | Literature | Britannica.” Accessed November 25, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/art/fiction-literature. |

| [^creanon]: “Historical Narratives | Creative Nonfiction.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://creativenonfiction.org/historical-narratives. |

References

“20 Quotes on Writing From Famous Authors.” Accessed November 5, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/what-is-writing-1689236.

“Academic Writing.” Wikipedia, November 6, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Academic_writing&oldid=924805383.

“Act Of Creation Quotes (5 Quotes).” Accessed November 6, 2019. https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/tag/act-of-creation.

“Alternate History.” Wikipedia, November 4, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alternate_history&oldid=924519761.

“Category:Alternate History Television Series.” Wikipedia, October 20, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Category:Alternate_history_television_series&oldid=864899833.

“Creative Nonfiction - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_nonfiction.

“Definition of ALTERNATIVE HISTORY.” Accessed November 25, 2019. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/alternative+history.

“Fiction.” Wikipedia, October 1, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fiction&oldid=919021848.

“Fiction - Dictionary Definition.” Vocabulary.com. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/fiction.

| “Fiction | Literature | Britannica.” Accessed November 25, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/art/fiction-literature. |

“Historical Fiction.” Wikipedia, November 5, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Historical_fiction&oldid=924773655.

| “Historical Narratives | Creative Nonfiction.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://creativenonfiction.org/historical-narratives. |

“Is Historical Fiction a Form of Non-Fiction? - Delphinium Books.” Accessed October 24, 2019. http://www.delphiniumbooks.com/is-historical-fiction-a-form-of-non-fiction/.

“List of Historical Novels.” Wikipedia, October 15, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=List_of_historical_novels&oldid=921389179.

“Narrative - Dictionary Definition.” Vocabulary.com. Accessed November 13, 2019. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/narrative.

“Narrative History.” Wikipedia, September 21, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Narrative_history&oldid=860511626.

“Narrative History - Wikipedia.” Accessed November 6, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Narrative_history.

“Narrative Nonfiction vs Historical Fiction.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://www.childrencomefirst.com/narrativenonfiction-historicalfiction.shtml.

“Nonfiction vs. Creative Nonfiction vs. Historical Fiction – Donna Janell Bowman.” Accessed October 23, 2019. https://www.donnajanellbowman.com/2010/08/25/nonfiction-vs-creative-nonfiction-vs-historical-fiction/.

“Uchronia: The Alternate History List.” Accessed November 6, 2019. http://www.uchronia.net/.

| “What Is Creative Nonfiction? | Creative Nonfiction.” Accessed November 7, 2019. https://www.creativenonfiction.org/online-reading/what-creative-nonfiction. |

“What Is the Relationship between History and Historical Fiction? - OpenLearn - Open University.” Accessed October 23, 2019. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/history-the-arts/creative-writing/what-the-relationship-between-history-and-historical-fiction.

Bowman, Donna Janell. “Nonfiction vs. Creative Nonfiction vs. Historical Fiction.” Donna Janell Bowman. Accessed October 22, 2019. https://www.donnajanellbowman.com/2010/08/25/nonfiction-vs-creative-nonfiction-vs-historical-fiction/.

Huskinson, Janet. “Looking for Culture, Identity and Power,” n.d., 25. https://www.open.edu/openlearn/ocw/pluginfile.php/613847/mod_resource/content/1/aa309_1_reading_001.pdf.

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. London; New York: Routledge, 2003.

McCullough, Colleen. Caesar. London : Head of Zeus, 2014.

———. The First Man in Rome. New York : Morrow, 1990.

———. The Grass Crown. New York : W. Morrow, 1991.

Mickel, Emanuel J. “Fictional History and Historical Fiction.” Romance Philology 66, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 57–96. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.RPH.5.100799.

O’Grady, Megan. “Why Are We Living in a Golden Age of Historical Fiction?” The New York Times, May 7, 2019, sec. T Magazine. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/07/t-magazine/historical-fiction-books.html.

Rosenberg, Alex. “Why Most Narrative History Is Wrong.” Salon, October 7, 2019. https://www.salon.com/2018/10/07/why-most-narrative-history-is-wrong/.

Sanger, Thomas. “Historical Fiction vs Narrative Nonfiction: What’s in a Genre?” Thomas Sanger. Accessed October 23, 2019. http://thomascsanger.com/thomas-c-sanger/historical-fiction-vs-narrative-non-fiction-whats-genre/.

Tod, M. K. “7 Elements of Historical Fiction.” A Writer of History, March 24, 2015. https://awriterofhistory.com/2015/03/24/7-elements-of-historical-fiction/.

———. “10 Thoughts on the Purpose of Historical Fiction.” A Writer of History, April 14, 2015. https://awriterofhistory.com/2015/04/14/10-thoughts-on-the-purpose-of-historical-fiction/.

Tolstoy, Leo. War and Peace. Oxford ; Oxford University Press, 2010.

Vallar, Cindy. “Historical Fiction vs. History.” Accessed October 24, 2019. http://www.cindyvallar.com/histfic.html.

-

“Narrative History.” Wikipedia, September 21, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Narrative_history&oldid=860511626. ↩

-

“Academic Writing.” Wikipedia, November 6, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Academic_writing&oldid=924805383. ↩

-

“Creative Nonfiction - Wikipedia.” Accessed October 24, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Creative_nonfiction. ↩

-

Sanger, Thomas. “Historical Fiction vs Narrative Nonfiction: What’s in a Genre?” Thomas Sanger. Accessed October 23, 2019. http://thomascsanger.com/thomas-c-sanger/historical-fiction-vs-narrative-non-fiction-whats-genre/. ↩

-

“Historical Fiction.” Wikipedia, November 5, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Historical_fiction&oldid=924773655. ↩

-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9vST6hVRj2A ↩

-

https://www.azlyrics.com/lyrics/gordonlightfoot/thewreckoftheedmundfitzgerald.html ↩

-

“Alternate History.” Wikipedia, November 4, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Alternate_history&oldid=924519761. ↩

-

“Category:Alternate History Television Series.” Wikipedia, October 20, 2018. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Category:Alternate_history_television_series&oldid=864899833. ↩

-

Mickel, Emanuel J. “Fictional History and Historical Fiction.” Romance Philology 66, no. 1 (January 1, 2012): 57–96. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1484/J.RPH.5.100799. ↩

-

“Fiction.” Wikipedia, October 1, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Fiction&oldid=919021848. ↩

-

“Fiction - Dictionary Definition.” Vocabulary.com. Accessed November 6, 2019. https://www.vocabulary.com/dictionary/fiction. ↩

-

Lemon, M. C. Philosophy of History: A Guide for Students. London; New York: Routledge, 2003. ↩

-

https://unm-historiography.github.io/intro-guide/essays/thematic/eurocentrism ↩

-

Tod, M. K. “10 Thoughts on the Purpose of Historical Fiction.” A Writer of History, April 14, 2015. https://awriterofhistory.com/2015/04/14/10-thoughts-on-the-purpose-of-historical-fiction/. ↩

-

“Is Historical Fiction a Form of Non-Fiction? - Delphinium Books.” Accessed October 24, 2019. http://www.delphiniumbooks.com/is-historical-fiction-a-form-of-non-fiction/. ↩

-

Rosenberg, Alex. “Why Most Narrative History Is Wrong.” Salon, October 7, 2019. https://www.salon.com/2018/10/07/why-most-narrative-history-is-wrong/. ↩